| ÒÊ ÑÍÒÒ |

| Ñòðóêòóðà | Ñêëàä | Àäðåñà | Çàñàäè | Ïðàâîïèñ | Êîíôåðåíö³ÿ | Ñåì³íàð | Òåðì³íîãðàô³ÿ | ³ñíèê | Òîâàðèñòâî | Êîì³ñ³ÿ | Îãîëîøåííÿ | Õòî º õòî | Àðõ³â |

ÇÁ²ÐÍÈÊ

íàóêîâèõ ïðàöü ó÷àñíèê³â XIV ̳æíàðîäíî¿ íàóêîâî¿ êîíôåðåíö³¿

«Ïðîáëåìè óêðà¿íñüêî¿ òåðì³íîëî㳿 ÑëîâîÑâ³ò 2016»

29 âåðåñíÿ – 1 æîâòíÿ 2016 ð.

¥àë³íñê³ Õ. Terminology and multilingual product masterdata management / Õðèñò³ÿí ¥àë³íñê³ // Ïðîáëåìè óêðà¿íñüêî¿ òåðì³íîëî㳿 : ì³æíàð. íàóê. êîíô., 29 âåðåñ. – 1 æîâò. 2016 ð. : çá. íàóê. ïð. ‒ Ë., 2016. ‒ Ñ. 44‒63.

ÓÄÊ 800

Õðèñò³ÿí ¥àë³íñê³

̳æíàðîäíèé ³íôîðìàö³éíèé òåðì³íîëîã³÷íèé öåíòð Infoterm, ì. ³äåíü, Àâñòð³ÿ

Òåðì³íîëîã³ÿ ³ áàãàòîìîâíèé ïðîäóêò êåðóâàííÿ ìàéñòåð-äàíèìè

(̳æíàðîäí³ ñòàíäàðòè äëÿ ñòðóêòóðîâàíîãî êîíòåíòó − íåîáõ³äíà óìîâà åëåêòðîííî¿ òîðã³âë³)

Christian Galinski

Infoterm, Vienna, Austria

Terminology and multilingual product masterdata management

(International Standards for structured content – A prerequisite of eCommerce)

© ¥àë³íñê³ Õ., 2016

Ìàéæå âñ³ ïðîäóêòè ëþäñüêî¿ ä³ÿëüíîñòè é ïîñëóã çíà÷íîþ ì³ðîþ º ñóá’ºêòîì «òåõí³÷íèõ ñòàíäàðò³â» − äðóãî¿ ï³ñëÿ çàêîíó ôîðìè ðåãóëþâàííÿ. Òàêèì ÷èíîì, äîñòàòí³ çíàííÿ ïðî ÷èíí³ ñòàíäàðòè é ïîòî÷íó ä³ÿëüí³ñòü ó ãàëóç³ ñòàíäàðòèçàö³¿ ìàþòü âàæëèâå çíà÷åííÿ äëÿ åôåêòèâíîãî âèêîðèñòîâóâàííÿ â åëåêòðîíí³é òîðã³âë³. Ùîá çàáåçïå÷èòè âçàºìîä³þ ì³æ ð³çíèìè çàñîáàìè, ñëóæáàìè é äàíèìè ðîçðîáëÿþòü íà ï³äñòàâ³ ì³æíàðîäíèõ ñòàíäàðò³â ³íôîðìàö³éíî-êîìóí³êàö³éí³ òåõíîëî㳿 (²ÊÒ, ICT). Öå ñòîñóºòüñÿ ëþäñüêî¿ êîìóí³êàö³¿ òà ìîâè, ðîëü ²ÊÒ ó ÿêèõ çðîñòàº. Ñòàíäàðòè óñòàëþþòü íà ð³çíèõ ð³âíÿõ: ¿õ ìîæå áóòè ðîçðîáëåíî çà äîïîìîãîþ ôîðìàëüíîãî ñòàíäàðòóâàííÿ àáî âåëèêèìè ãàëóçåâèìè ÷è ïðîìèñëîâèìè êîðïîðàö³ÿìè ó âèãëÿä³ ð³çíîòèïíèõ äîêóìåíò³â, òàêèõ ÿê ñïåöèô³êàö³¿, òåõí³÷í³ çâ³òè, êîäåêñè óñòàëåíî¿ ïðàêòèêè. Âîíè ìîæóòü ñòîñóâàòèñÿ ïðîäóêò³â, ïðîöåñ³â, ïîñëóã, òåðì³íîëî㳿, ìåòîäîëî㳿, òåñòóâàííÿ, ð³çíèõ êîä³â, ³íòåðôåéñ³â òîùî, ÿê³ îõîïëþþòü óñ³ öàðèíè æèòòÿ.  åëåêòðîíí³é òîðã³âë³ êåðóâàííÿ îñíîâíèìè ìàéñòåðäàíèìè (MDM) ç óñ³ìà âèäàìè êîíòåíòó (íàïðèêëàä, áàãàòîìîâíèé îïèñ ³ êëàñèô³êàö³ÿ ïðîäóêòó é ïîâ’ÿçàí³ ç ìîâíèìè òåõíîëîã³ÿìè − LT) ðåãóëþþòü íîðìàìè, ÿê³ ìàþòü çíàòè ²Ò-ïåðñîíàë ³ êåð³âíèöòâî.

Êëþ÷îâ³ ñëîâà: òåðì³íîëîã³ÿ, ñòàíäàðòóâàííÿ, ñòàíäàðò, ³íôîðìàö³éíî-êîìóí³êàö³éí³ òåõíîëî㳿, êåðóâàííÿ ìàéñòåðäàíèìè, åëåêòðîííà òîðã³âëÿ.

Without being much aware of it, nearly all human products, services and activities are largely subject to ‘technical standards’ – a form of regulation second only to law. Therefore, a sufficient knowledge on existing standards and ongoing standardization activities is important for using eCommerce effectively. For the sake of interoperability of devices, services and data, information and communication technologies (ICT) are strongly based on international standards. This applies also to human communication and language which are increasingly ICT-assisted. Standards are established at different levels and may be developed through formal standardization or by big industry or industry consortia in the form of different types of documents, such as specifications, technical reports, codes of practice. They may refer to products, processes, services, terminology, methodology, testing, various codes, interfaces, etc. affecting all walks of life. In eCommerce, master data management (MDM) with all kind of content (such as multilingual product description and classification and the related language technology – LT) is governed by standards which should be known by IT personnel and management alike.

Keywords: terminology, standardization, standard, information and communication technologies, master data management, eCommerce.

Introduction

Although most of us are not aware of it, our life is as much influenced by standards as it is ruled by law. This contribution shows the relationship between different kinds of standards developed by different kinds of standards developing organizations (SDO), the importance of content and communication in eCommerce/eBusiness (eC/eB), as well as language in conjunction with today’s eC/eB.

A huge amount of content (i.e. information) is generated in the form of structured or unstructured content and communicated – as much as possible automatically – in the form of data exchange or messages daily in today’s commerce and trade. This content and the methods as well as technologies used are subject to a high degree of standardization with respect to content itself, messaging, processes, interfaces and the respective methodologies applied. In this connection it is necessary to mention that no distinction is made between data, information and content in daily practice (although they are different in fundamental computer science theory). In practice, information is all content from the user’s perspective, while it is all data from the computer programmer’s perspective [Boiko 2004].

Starting off with core aspects of eC/eB this contribution deals with the complex world of standardization, the manifold facets of content in eC/eB and is drawing conclusions from latest research and development (R&D) trends.

1. eCommerce and content related standards

World-wide, there are many systems supporting eC/eB which are not compatible from a system point of view, but must be fully interoperable from a content and communication point of view. eCommerce refers to the trading in products or services using computer networks, comprising first of all the Internet, and drawing on technologies such as mobile commerce, electronic funds transfer, supply chain management, Internet marketing, online transaction processing, electronic data interchange (EDI), inventory management systems, and automated data collection systems. eBusiness refers to the application of information and communication technologies (ICT) in support of all the activities of business – including commerce as one of the essential activities of any business. eBusiness obviously has the broader scope, while eCommerce enters deep into the intricacies of data models and communication with respect to the trading of products or services. In this contribution eC/eB is used as a collective term covering both.

eProcurement covers a certain spectrum of processes under eCommerce. “Although there is a basic distinction between procurement in the public and private sectors according to the process steps which have to be fulfilled for purchasing; the following steps are necessary for all eProcurement in general:

● eSourcing contains all preparatory activities conducted by the contracting authority (CA) to collect and reuse information for the preparation of a call.

● eNoticing or eNotification is the advertisement of calls for tenders through the publication of appropriate contract notices in electronic format in the relevant Official Journal (national/EU). This includes electronic access to tender documents and specifications, and additional related documents provided in a non-discriminatory way.

● eAccess means the electronic access to tender documents and specifications as well support to economic operators (EO) for the preparation of an offer, e.g. clarifications, questions and answers.

● eSubmission is the submission of offers in electronic format to the CA, which is able to receive, accept and process it in compliance with the legal requirements.

● eTendering means the union of the eAccess and eSubmission phases.

● eAwarding comprises the opening and evaluation of the electronic tenders received, as well as the award of the contract to the best offer in terms of the lowest price or economically most advantageous bid.

● eContracting is the phase of conclusion, enactment and monitoring of a contract through electronic means between the CA and the winning tenderer.

● eOrdering phase contains the preparation and issuing of an electronic order by the CA and its acceptance by the contractor.

● eInvoicing is the preparation and delivery of an invoice in electronic format.

● ePayment covers the electronic payment of the ordered goods, services or works” [Galinski/Beckmann 2011 based on CWA 15236, CWA 15666].

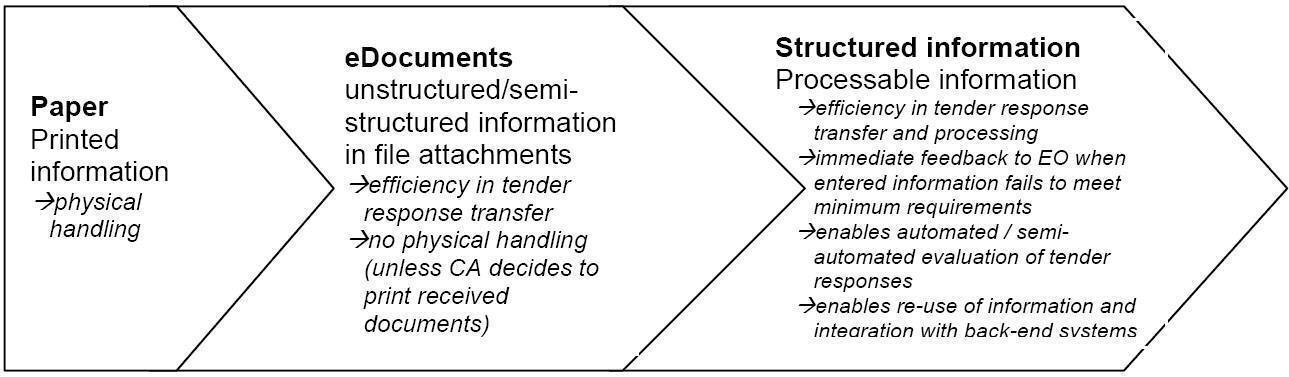

In 2012, the European Commission set up an informal eTendering Expert Group (eTEG) which was tasked with defining a blueprint for pre-award eProcurement that ensures wide accessibility including cross-border procurement, SME’s (small and medium-sized enterprises’) inclusiveness, wide interoperability, transparency, traceability and accountability. Multilinguality of content in this connection goes without saying. The eTEG report and recommendations set out to define a transition path from a predominantly unstructured document-oriented approach towards a structured information-oriented model. The overall objective was to provide the EOs of enterprises with enhanced ease-of-use through a standards-based way of interacting with eTendering platforms, while also enhancing the functionality for CAs, for example automatic processing and evaluation of tender responses in the direction of system-to-system information exchange [http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/publicprocurement/e-procurement/expert/index_en.htm].

The more procurement systems develop towards harmonization/interoperability at national level and cross-border application (incl. the need for localizing systems and data), the more aspects of eC/eB have to be based on international standards. This includes methodology standards of all sorts and content/data standards, as well as standards on data quality and content interoperability. This triggers needs for new staff competences and skills, as well as the respective training and certification schemes – (preferably) all based on standards.

2. Impact of standards and standardization on eC/eB

The “Investigation of industry&business-relevant standards and guidelines in the fields of the language industry” [Infoterm 2012] stated how standards can help enterprises:

● To clearly define their requirements and specifications in conjunction with

o the outsourcing of language services (LS) to language service providers (LSP),

o the development or adaptation of language technology tools/systems (LTT) as well as of language and other content resources (LCR);

● To refer to the pertinent standards in tenders or bids or contracts of all sorts;

● To state their competences/skills (or that of their staff) in compliance with standards;

● To make their quality management transparent and understandable for their customers;

● To become more competitive in an increasingly multilingual world.

Using standards properly in the above-mentioned way can help to avoid misunderstandings, undesirable mistakes and conflicts, risks and even liabilities. Therefore, a sufficient knowledge about international standards – and the legal implications, certification schemes based on standards, impact on necessary staff competences and skills, etc. – in enterprises is essential today.

2.1 How are standards developed?

Standardization is an activity for establishing, with regard to actual or potential problems, provisions for common and repeated use, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context. In particular, the activity consists of the processes of formulating, issuing and implementing standards. Important benefits of standardization are improvement of the suitability of products, processes and services for their intended purposes, prevention of barriers to trade and facilitation of technological cooperation [ISO/IEC Guide 2].

Harmonization <in standardization> is the activity to align existing standards or other technical regulations, if there are inconsistencies or contradictions between them, whether within the same technical committee (TC), between TCs of the same field or between different standardizing organizations. Harmonized standards establish interchangeability of products, processes and services, or mutual understanding of test results or information provided according to these standards. Within this definition, they might have differences in presentation and even in substance, e.g. in explanatory notes, guidance on how to fulfill the requirements of the standard, preferences for alternatives and varieties. [ISO/IEC Guide 2]

Many experts – especially in the fields of the humanities and social sciences (not to mention arts) – consider standardization as an obstacle to ‘creativity’ and ‘innovation’. However, given the ever-increasing complexity of the world we are living in, standardization can also be considered as a way of dynamic coding of the essence of human knowledge and experience. In industry the value of standardization as a strong factor of innovation is fully recognized.

Formal standardization activities are governed by highly systemic approaches and rules. The preparation of standards is based on consensus, which is a general agreement, characterized by the absence of sustained opposition to substantial issues by any important part of the concerned interests and by a process that involves seeking to take into account the views of all parties (namely industry, research, public administration, consumers) concerned and to reconcile any conflicting arguments [ISO/IEC Guide 2].

There are many standards developing organizations (SDO) at different levels: international, regional, national – sometimes even provincial. The formal standardizing organizations at international level are:

● ISO, the International Organization for Standardization,

● IEC, the International Electrotechnical Commission,

● ITU, the International Telecommunication Union.

For eC/eB the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) is also recognized as formal international standardizing organization. There are similar more or less authoritative international SDOs in other areas or sub-fields.

With respect to the ICT there is the Joint Technical Committee ISO/IEC-JTC 1 “Information Technology” developing many of the general standards for all or most of the ICT. Increasingly other TCs of ISO, IEC and ITU responsible for eBusiness, eHealth, eLearning and the like are also developing technical standards having a bearing on the whole of ICT, in general, and eC/eB, in particular.

Some of the ICT-related standards are developed by organizations of high authority, such as:

● World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and in particular its Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF),

● Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

However, a substantial number of ICT-related standards are ‘industry standards’ developed by industry consortia. Many of these claim to develop ‘open’ standards in the meaning of ‘free-of-charge’ standards. Most of these SDOs are active in specific domains – some at international, some at regional level –, others just work for some members of the respective branch of industry.

At regional level there are standardizing organizations, such as

● Three European standardization organizations (ESO) issuing technical standards: CEN (European Committee for Standardization), CENELEC (European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization) and ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute),

● COPANT, the Pan American Standards Commission (in Spanish: Comisión Panamericana de Normas Técnicas), which is a civil, non-profit association whose basic objective is to promote the development of technical standardization and related activities in its member countries with the aim of promoting their industrial, scientific and technological development in benefit of an exchange of goods and the provision of services, while facilitating cooperation in intellectual, scientific and social fields.

The standards issued by the ESOs are recognized as international standards by the formal international standardizing organizations and vice versa.

At national level usually national standards bodies or official standardization organizations (including government agencies) are members of ISO and/or IEC, or ITU.

The variety of regulations governing standardization mirrors the complexity of the system of standards organizations. In some cases there are legal provisions concerning standardization, in many cases there are standards documents governing standardization which can be called meta-standards, such as the ISO/IEC Directives. In addition, big efforts are undertaken to harmonize existing open standards at national, regional and international levels so that they do not compete with or even contradict each other, which is unacceptable among others according to the WTO (World Trade Organization) Agreement. The “Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade” (TBT Agreement) – sometimes referred to as the “Standards Code” – is one of the legal texts of the WTO Agreement which obliges WTO Members to ensure that technical regulations, voluntary standards and conformity assessment procedures do not create unnecessary obstacles to trade. Annex 3 of the TBT Agreement is the “Code of Good Practice for the Preparation, Adoption and Application of Standards” which is also known as the “WTO Code of Good Practice”.

In accepting the TBT Agreement, WTO Members agree to ensure that their central government standardizing bodies accept and comply with this Code of Good Practice and also agree to take reasonable measures to ensure that local government, non-governmental and regional standardizing bodies do the same.

The organizations mentioned so far usually conduct their standardization work in committees, often called technical committee (TC) that mostly emerge in the wake of expressed needs for standards. Most often these TCs are quite independent to define their own scope and work program. If they deal with many standards, the work is often distributed to sub-committees (SC) and working groups (WG) or the like. Regularly the standardizing activities are better coordinated within a standardizing organization or SDO than between different SDOs – although the experts working in the committees are usually networking across organizations thus informally coordinating the development of standards. But given this situation, some overlaps and at the same time gaps or even conflicting formulations are inescapable.

2.2 What kinds of standards impact eC/eB?

Technical standards are more or less mandatory regulations second only to law. If a law refers to a technical standard as an obligatory requirement, this standard becomes part of the law itself. Technical standards comprise a whole range of different kinds of documents which can be categorized in various ways depending on the distinguishing criteria. Accordingly, they may constitute different sorts of text.

From the point of view of kinds of standards documents (of more or less binding nature) there are for instance in ISO: International Standards (IS), Technical Specifications (TS), Publicly Available Specifications (PAS), Technical Reports (TR) – not to forget the meta-standards already mentioned concerning standar-dization itself, such as:

● the ISO/IEC Directives (in two parts with several Annexes each) for the whole of standardization in ISO and IEC,

●

ISO/IEC Directives,

Supplement. Consolidated procedures specific to ISO (2014)

[including also Annex SQ (normative) Procedures for the standardization of

graphical symbols and Annex SK (normative) Procedure for the development and

maintenance of standards in database format],

● ISO/IEC Directives,

IEC Supplement, Procedures specific to IEC (2012)

[including also Annex SK (normative) Implementation of the ISO/IEC Directives

for the work on the IEC 60050 series – International Electrotechnical

Vocabulary],

● ISO/IEC Guide 2:2004 Standardization and related activities – General vocabulary,

● ISO/IEC Directives, Supplement. Procedures specific to JTC 1 (2010),

● ISO/IEC Guide 21-1:2005 Regional or national adoption of International Standards and other International Deliverables – Part 1: Adoption of International Standards,

● ISO/IEC Guide 21-2:2005 Regional or national adoption of International Standards and other International Deliverables – Part 2: Adoption of International Deliverables other than International Standards.

In addition, there are numerous ISO/IEC guides for major fields of standardization or important aspects touching upon several fields of standardization.

From the point of view of subject content, one can distinguish broadly between methodology standards and subject standards (each for a certain topic – multipart standards deal with different specific issues under a broader topic). Another broad distinction is between ‘basic’ (or fundamental or general or horizontal) standards and specific standards. Basic standards are important for large areas of standardization or for standardization as a whole, such as standards on terminological methodology.

Standardization started off from technical standards proper, e.g. concerning ‘hardware’ and ‘software’ in the traditional sense. Today, the majority of standards are considered as methodology standards. However, the number of content/data standards is rapidly increasing.

Subject standards can be further distinguished into:

● Terminology standards (or a part on terms and definitions in subject standards),

● Product/process/service standards,

● Interface standards,

● Testing standards,

● Standards on data to be provided,

● Standardized coding systems,

● Data/content standards.

Many existing standards are a mixture of the above – for instance coding standards often comprise the coding methodology and the codes based on the respective methodology. In conjunction with the rapidly emerging eApplications the number of data standards is increasing exponentially – among others for the sake of ‘semantic interoperability’.

Usually all standards documents have to comply with regular review and revision processes. This is different in the case of standardized codes – which mostly are maintained and updated in databases under the responsibility of a registration authority (RA) or maintenance agency (MA): once a code symbol is assigned it should never be replaced by another. Code symbols can be retired or considered deprecated, but should never be re-used.

2.3 How to achieve compatibility, integration and interoperability?

As for the ICTs, compatibility today is taken for granted – or not necessary in each case, if for instance interoperability is provided. The eXtendable Markup Language (XML) can establish basic compatibility of data, but not necessarily content interoperability. System and content integration are strong requirements today to reduce the number of stand-alone systems in enterprises containing among others legacy data in different formats which causes cost and all kinds of technical problems. Interoperability in fact is addressing the semantics of content – however, semantics from the point of view of inter-human communication and semantics from a computer science point of view are (still) quite different.

From the point of view of linguistics, semantics distinguishes between several levels:

● Lexical semantics,

● Sentence semantics,

● Text semantics,

● Discourse semantics.

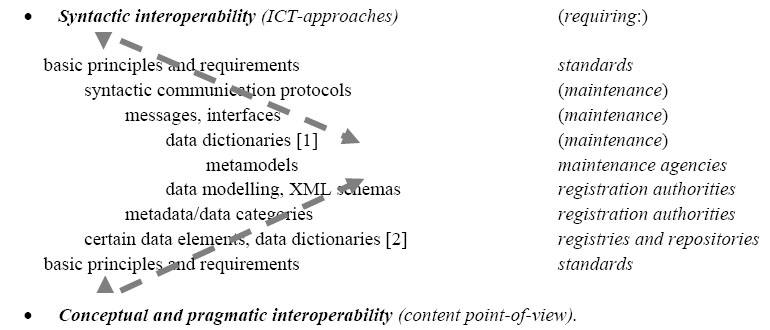

Entities of structured content or ‘microcontent’ are at the basic level of lexical semantics. However, this basic level itself can be quite complex and for the sake of true semantic interoperability it needs more than syntactic interoperability, namely also conceptual and pragmatic interoperability. Taken together this content interoperability can hardly be achieved without organizational interoperability. [Galinski 2006]

Ultimately any content in whatever form (at least potentially) has to be understood by human beings. Content interoperability is also comprising re-purposability (e.g. for teaching and training purposes) and probably requires human intervention. It goes without saying that at the end of information processing, humans may have to take decisions which should be based on sound reasoning. Therefore, the approaches of computer science and of linguistics should be made interoperable also from the point of view of methodology. This certainly calls for standards.

The following figure can guide towards an approach to achieve the above-mentioned interoperability of methodologies [Galinski 2005]:

In connection with the above, the term ‘dictionary’ causes misunderstanding as it stands for quite different concepts in computer science and in linguistics.

It is increasingly recognized today that content interoperability goes beyond the concept of semantic interoperability between computer systems (‘computable semantic interoperability’). Content interoperability with respect to structured content at the level of lexical semantics (viz. microcontent) is the capability of microcontent entities (i.e.) to be:

● integrated into or combined with other (types of) content entities;

● extensively re-used for other purposes (also sub-entities to be re-purposable);

● searchable, retrievable, re-combinable from different points-of-view

[Galinski/Van Isacker 2010].

In order to be fully localizable, content must be multilingual and multimodal from the outset as stated by the “Recommendation on software and content development principles 2010” (see Annex). Why is standardization so important in this connection?

Ultimately only the international standards of ISO, IEC and ITU as well as the guidelines of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) can guarantee the most efficient use, re-use and re-purposing of structured content across languages and system platforms.

The efficient use, re-use and re-purposing at the place of use can only be realized, if two fundamental principles of content management methodology are thoroughly followed: single sourcing and resource sharing. These methodological principles – if not based on formal standards – must be ensured by an organization-wide unified methodology and guaranteed by system architectures based on this methodology.

3. What are content related standards?

This part concentrates on content aspects in relation to standardization. Here a distinction between primary and secondary standards can be made.

3.1 Basic and secondary content-related standards

From the point of view of content standardization – focusing on eContent – the following standards can be regarded as secondary, however, fundamental standards:

● Basic standards of language industry (LI) related ICT (such as character/glyph coding, keyboard layout, cultural specific ICT requirements, OCR – optical character recognition, script conversion, speech to written conversion, etc.),

● Basic standards for data processing (including quality management, fundamentals of data modeling, etc.),

● Generic formats (e.g. XML), protocols and schemas,

● Information and documentation (meta-information) standards,

● General standards related to mobility and accessibility.

Again from the point of view of content standardization, standards on the following aspects have to be regarded as primary:

● Language and other content resources (LCR),

● Content processing by means of language technology tools (LTT),

● Content use e.g. through services (incl. language service providers, LSP).

3.2 Methodology standards for language and other content resources (LCR)

According to ELRA (European Language Resource Association) language resources are:

● Text corpora

● Speech corpora

● (Lexicographical data and) Terminologies

Given the fact that content resources

● are of many different kinds,

● are not confined to language resources,

● may comprise or even consist of non-linguistic content (logos, formulas, icons, audiovisual content, etc.),

it is more appropriate to broadly subdivide them into LCR of unstructured content and LCR of structured content and then look at the respective methodology standards.

3.2.1 Methodology standards related to unstructured content (semi-structured content)

The most well-known kinds of unstructured content are:

● Running text (in all kinds of literature, scientific-technical texts, in the print media, etc.),

● Speech corpora,

● Music of all sorts,

● Film, video, audiovisual and multimedia content, etc.

Some of these are tagged or marked-up for further processing or application, such as text and speech corpora. Concerning texts, the Consortium of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) collectively develops and maintains a standard for the representation of texts in digital form, namely the “TEI Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange”. These Guidelines define and document a markup language for representing the structural, renditional, and conceptual features of texts by specifying encoding methods for machine-readable texts. They are expressed as a modular, extensible XML schema, accompanied by detailed documentation, and are published under an open-source license [http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/].

TEI also had a big impact on the standardization of various aspects of structured content – among others in the form of the establishment of the sub-committee ISO/TC 37/SC 4 Language resources management. The TEI Guidelines certainly helped to make LI approaches like translation memory (TM), parallel texts, bitexts, machine translation (MT) and various forms of semi-automatic translation, etc. more efficient. This in turn facilitated the development of new services in the LI.

Another promising field of standardization is controlled natural language (CNL) which emerged out of simplified language approaches. ISO/TC 37/SC 4 recently finalized ISO/TS 24620-1 “Language resource management – Controlled natural language (CNL) – Basic concepts and general principles”. This emerging series of standards will facilitate the development or adaptation of authoring tools which among others would make the pre-editing of texts for machine translation (MT) more effective.

3.2.2 Methodology standards related to (semantically) structured content

Whatever the approaches, entities of microcontent are the building elements of unstructured content. Galinski/Reineke [2011] made an attempt to quantify the volumes of lexicographical and terminological entries in an ever increasing number of domains or subjects. In highly developed languages the lexis of general purpose language (GPL) may comprise about 500,000 lexemes (including a considerable share of terminology). However, the total number of scientific-technical concepts across all domains or subjects may well comprise 100~150 million. The volumes of existing proper names and other kinds of appellations, some of which may be subject to translation into other languages or conversion into other scripts, may amount to a multitude of the above figures [Infoterm 2012 CELAN 2.1 Annex 2].

These amounts of microcontent – more often than not with different language versions – pose a huge challenge to software and content developers as well as LSP. The industry customers – especially SMEs – most probably are usually unaware of the quantitative and qualitative phenomena related to LCR.

Entities of microcontent may comprise linguistic and non-linguistic representations of concepts, which can be designative (such as designations in terminology: comprising terms, symbols and appellations) or descriptive (such as various kinds of definitions or non-verbal representations), or hybrid. Standards or guidelines in this category may refer to the methods of language resource management or may contain standardized (or otherwise regulated) content items (such as standardized vocabularies) [Infoterm 2012 CELAN 2.1 Annex 2].

With respect to LCR-related methodology, the standards of the technical committee ISO/TC 37 “Terminology and other language and content resources” underwent big changes over the last years. Starting off with less than 10 standards in the 1980s, they developed into a comprehensive system covering rules for:

● The whole of structured content in standardization activities,

● Specific individual kinds of standardized structured content (such as standardized terminology),

● The management of standardized or not-standardized structured content (incl. data modeling standards focused on terminology and other language resources),

● Data quality and content interoperability of LCR.

The importance of the latter is increasingly recognized in content management of structured content (e.g. for Web content management systems). Typical in standardization today, many of the above-mentioned standards, in fact, combine categories of standards documents or contain standardized structured content developed by using the methodology they outline.

Concerning microcontent the primary basic methodology standards in ISO/TC 37 and ISO/TC 46 “Information and documentation” are among others:

● ISO 704:2009 Terminology work – Principles and methods (again under revision),

● ISO 860:2007 Terminology work – Harmonization of concepts and terms,

● ISO 1951:2007 Presentation/representation of entries in dictionaries – Requirements, recommendations and information,

● 10241-1:2011 Terminological entries in standards – Part 1: General requirements and examples of presentation,

● ISO 10241-2:2012 Terminological entries in standards – Part 2: Adoption of standardized terminological entries,

● ISO 12199:2000 Alphabetical ordering of multilingual terminological and lexicographical data represented in the Latin alphabet,

● ISO 12615:2004 Bibliographic references and source identifiers for terminology work [based on ISO 690 and ISO 2709],

● ISO 12620:2009 Terminology and other language and content resources – Specification of data categories and management of a Data Category Registry for language resources (DCR),

● ISO 15188:2001 Project management guidelines for terminology standardization,

● ISO/CD 17347 Ontology Integration and Interoperability (OntoIOp),

● ISO 21829 Terminology for language resources (under development),

● ISO 23185:2009 Assessment and benchmarking of terminological resources – General concepts, principles and requirements,

● ISO 25964-1:2011 Information and documentation – Thesauri and interoperability with other vocabularies – Part 1: Thesauri for information retrieval.

(ISO/TC 37/SC 4 standards for syntactic and semantic annotation:)

● ISO 24610 (multipart) Language resource management – Feature structures,

● ISO 24611 Language resource management – Morpho-syntactic annotation framework (MAF),

● ISO 24612:2012 Language resource management – Linguistic annotation framework (LAF),

● ISO 24613:2008 Language Resource Management – Lexical Markup Framework (LMF),

● ISO 24615:2010 Language resource management – Syntactic annotation framework (SynAF),

● ISO 24617 (multipart) Language resource management – Semantic annotation framework (SemAF).

Increasingly other TCs and organizations that standardize structured content of similar authority, like TCs in standardization, embark on describing their methodology in a prescriptive way for the sake of content interoperability. In many cases the standards comprise also the standardized terminology necessary to understand the respective methodology. Such standardizing committees are among others:

● ISO/IEC-JTC 1/SC 32/WG 2 MetaData,

● ISO/IEC-JTC 1/SC 36 Learning technologies,

● ISO/TC 145 Graphical symbols,

● ISO/TC 154 Processes, data elements and documents in commerce, industry and administration,

● ISO/TC 184/SC 4 Industrial data,

● ISO/TC 215 Health informatics.

These and other TCs develop methodology standards about metadata necessary to manage all kinds of collections of structured content, such as:

● ISO 9735 (multipart) Electronic data interchange for administration, commerce and transport (EDIFACT) [ISO/TC 154 Processes, data elements and documents in commerce, industry and administration],

● ISO 11179 (multipart) Information technology – Metadata registries (MDR) [ISO/IEC-JTC 1/SC 32/WG 2 MetaData],

● ISO 13584 (multipart) Industrial automation systems and integration – Parts library (PLIB) [ISO/TC 184/SC 4 Industrial data],

● ISO 15836:2009 Information and documentation – The Dublin Core metadata element set [ISO/TC 46],

● ISO/IEC 19788:2012 (multipart) Information technology – Learning, education and training – Metadata for learning resources [ISO/IEC-JTC 1/SC 36 Learning technologies],

● ISO/IEC TR 20007:2014 Information technology – Cultural and linguistic interoperability – Definitions and relationship between symbols, icons, animated icons, pictograms, characters and glyphs [ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 35 User interfaces].

However, there are also other organizations beyond the standardization framework that standardize certain kinds of microcontent in specific domains, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) with its family of international classifications (WHO-FIC). WHO also outlines the respective methodologies and the processes involved in the maintenance and updating of the respective LCRs. This applies first of all to WHO’s main reference classifications:

● International Classification of Diseases (ICD),

● International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),

● International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI),

as well as its derived and related classifications [http://www.who.int/classifications/en/].

Sometimes competing – but each being considered as ‘authoritative’ – classification schemes exist and need mapping. In 2013, the CEN Workshop CEN/WS/eCAT “Multilingual eCataloguing and eClassification in eBusiness” developed the publicly available CEN Workshop Agreement CWA 16525:2012 “Multilingual electronic cataloguing and classification in eBusiness – Classification Mapping for open and standardized product classification usage in eBusiness”, together with the classification mapping tables which mapped – as far as it was possible the following international product classification schemes:

● UNSPSC v11 (English) of GS1 US,

● eCl@ss 6.0.1 (English) of eCl@ss e.V.,

● GPC 30062008 (English) of GS1,

● CPV 2008 (English) of the EU Commission.

CWA 16525:2012 outlines the methodology used. It is based on a series of other CWAs developed in previous standardization projects.

Methodology standards concerning metadata and similar are fundamental for a consistent approach to the following kinds of structured content of a meta-nature which categorize and specify the structured content (also called reference data or other names) they refer to:

● Metadata (defined by ISO/IEC 11179-1 as data that defines and describes other data),

● data categories (or data element type defined by ISO 1087-2 as a result of the specification of a given data field),

● Data elements (defined by ISO/IEC 11179-1 as unit of data for which the definition, identification, representation and permissible values are specified by means of a set of attributes),

● Data element concepts (defined by ISO/IEC 11179-1 as concept that can be represented in the form of a data element, described independently of any particular representation),

● Data dictionaries (or IRD, information resource dictionary, defined by ISO/IEC 2382-19:1999 as database that contains metadata).

From a formal point of view metadata and the like are also structured content, however, with additional functions. No wonder that the respective standards also standardize the metadata for the description and maintenance of metadata.

The above shows that the standards on methodology concerning structured content as well as the standardized LCRs themselves constitute a sort of self-referential system which today is more and more converging towards an overall consistency and coherence. The demand and requirements for content integration and interoperability is driving this system in the direction of a comprehensive interoperability of standards (incl. the interoperability of standardized methods).

3.3 Standardized language and other content resources (LCR)

For the sake of content integration and interoperability, approaches are increasingly geared towards defining and describing the smallest semantic entities which need standardization together with the respective methods. These smallest units today are named ‘microcontent’ or ‘structured content at the level of lexical semantics’ [Galinski/Giraldo 2013]. Each microcontent entity potentially can become a learning object for teaching/learning and training. Consequently the term micro learning object (mLO) was born. In this sense, all the standards so far mentioned can be considered as fundamental also for eLearning.

Galinski/Giraldo [2013] summarized: “Microcontent (in the sense of structured content at the level of lexical semantics) indicates content that conveys one primary idea or concept” and may cover the following kinds of entities:

|

Designative concept representation |

Descriptive concept representation |

Possible extensions |

|

(1) Terminological data: |

||

|

Linguistic designations: |

||

|

▪

terms

(incl. single-word and multi-word term) and similar, such a synonym,

antonym, equivalent (in another language), etc. |

▪ logic / partitive / other kind of determination ▪ logic / partitive / other kind of explanation ▪ other kind of linguistic descriptive representation |

▪ terminological phrasemes (focused on LSP communication entities) |

|

▪

abbreviated forms

(incl. initialisms, acronyms, clippings etc.) |

▪ terminological phrasemes (comprising an abbreviated form) |

|

|

▪

alphanumeric symbols |

▪ terminological phrasemes (comprising an alphanumeric symbol) |

|

|

· proper names (as kind of linguistic designation) |

|

· combinations of proper names with other linguistic designations |

|

Non-linguistic designations: |

||

|

▪ graphical symbols |

▪ graphical {descriptive} repre-sentation (more or less systemic) ▪ other kind of non-verbal descriptive representation (more or less systemic) |

▪ combinations of linguistic and non-linguistic/non-verbal designations |

|

▪ other visual symbols (incl. bar code, etc.) |

||

|

▪ non-visual non-linguistic symbols |

||

|

|

|

▪ combinations of all kinds of designations |

|

(2) Lexicographical data: |

||

|

▪ word (or similar entities) |

▪ (different kinds of) explanations |

|

|

▪ collocations (or similar entities) |

▪ micro-utterances (or similar entities) |

|

|

▪ non-verbal communication entities |

▪ (different kinds of) non-verbal explanatory representations |

▪ entities of alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) |

|

▪ other kinds of entities of inter-human communication |

|

|

|

|

|

▪ combinations of terminological and lexicographical data ▪ combinations with entities of inter-human communication |

|

(3) Controlled vocabularies: |

||

|

▪ thesaurus entries |

▪ indications of conceptual structure as well as of domain/subject ▪ other kinds of necessary indications |

▪ extensive mapping of controlled vocabularies |

|

▪ classification entries |

||

|

▪ entries of other kinds of controlled vocabularies |

||

|

(4) Data categories (metadata): |

||

|

▪ names of data categories |

▪ formal/coded description of data categories ▪ additional (incl. non-formal/ coded) elements of description |

▪ networking of repositories / registries of metadata and data categories |

|

(5) Coding systems (in eApplications) |

||

|

▪ standardized coded entities ▪ non-standardized coded entities |

▪ proper names (e.g. country, language, currency codes) ▪ product master data (incl. product classification codes) ▪ codes messages in eCommerce |

▪ rules for the combination of these in various applications

|

Today, one could add to this table:

|

(6) Other kinds of microcontent entities: |

||

|

▪ micro-blogs |

micro-statements or questions |

All of these and the above: ▪ can be combined to larger content entities ▪ are or should be potentially multi-lingual ▪ should be based on one or a few (preferably standardized) generic datamodels ▪ should be potentially interoperable ▪ may have different degrees of complexity ▪ must be re-usable and should also be re-purposable |

|

▪ weather forecast elements |

micro-statements |

|

|

▪ content elements of websites |

themes, sub-themes and micro-statements |

|

|

▪ elements of timetables (e.g. in public transport) |

facts and micro-statements (e.g. “delayed”) |

|

|

▪ instant messages |

themes, sub-themes and micro-statements |

|

|

▪ headlines |

themes and sub-themes |

|

|

▪ e-mail headings |

themes and facts |

|

|

▪ RSS feeds |

facts and micro-statements |

|

|

▪ Q&A schemes |

short questions and micro-statements or facts |

|

|

▪ bank credit cards details |

numbers, customer data |

|

|

▪ insurance / mortgage details |

facts, numbers, customer data |

|

|

▪ telephone directory details |

facts and numbers |

|

|

▪ online marketplace and catalogue details |

product-related data |

|

|

▪ content elements of PPT presentations |

structured or unstructured pictorial elements, text elements etc. |

|

|

▪ … |

|

|

Under a generic approach based on terminological data modeling methods all of the above may be varieties of one or a few (preferably standardized) generic datamodels for microcontent. In this connection, paradoxically, a higher granularity of data categories – which is perceived as high complexity by users – is not a higher degree of complexity for programmers. On the contrary, they consider a highly granular and systematic datamodel as “flat”.

3.4 New needs for content standardization: persons with disabilities (PwD)

More and more, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC – for persons with impairments in the production or comprehension of spoken or written language) is using ICT for syntactically and semantically structuring the communication process. Originally developed for and used by those with a wide range of speech and language impairments, advances in ICT, including speech synthesis, have paved the way for communication devices with speech output and multiple options for access to communication for those with physical disabilities. AAC systems are diverse: unaided communication uses no equipment and includes signing and body language, while aided approaches use external tools and range from pictures and communication boards to speech generating devices. The symbols used in AAC include gestures, photographs, pictures, line drawings, letters and words, which can be used alone or in combination. As message generation is generally much slower than spoken communication, rate enhancement techniques may be used to reduce the number of selections required. These techniques include ‘prediction’, in which the user is offered guesses of the word/phrase being composed, and ‘encoding’, in which longer messages are retrieved using a prestored code. In fact some of the regular functions of mobile devices today emerged from this field of assistive technologies (AT).

AAC microcontent in most cases is not fundamentally different from other kinds of microcontent, but it is adapted and applied for specific purposes. So in principle it should also fit into the above-mentioned one or a few (preferably standardized) generic datamodels. These datamodel(s) thus would cover communication in human language as well as interhuman communication in other modalities.

3.5 Microcontent in product master data management (PMDM)

Modern product information management (PIM) – under the requirement of content integration and interoperability – comprises among others multi-domain master data management (MDM). Formally, master data are in fact microcontent or are composed of microcontent. Product master data management (PMDM) is one kind of master data and comprises all kinds of information on products, such as properties, measurements (metric and possibly imperial or other), article numbering, (multiple) product classification, etc. It may also include data for business-to-business (B2B) exchange and other trade-related data. Thus it comprises many of the above-mentioned kinds of microcontent – down to different ways of presentation (up to multi-channel – including display on mobile devices).

The more PMDM data are based on international standards, the more international trade and other kinds of cooperation are facilitated. Master data include a lot of internationally coded data, such as:

● Country codes (acc. to multipart ISO 3166 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions),

● Currency codes (acc. to ISO 4217:2008 Codes for the representation of currencies and funds),

● Language codes (acc. to multipart ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages),

● Script codes (acc. to ISO 15924:2004 Information and documentation – Codes for the representation of names of scripts),

● Quantities and measures (acc. to multipart ISO 80000/IEC 80000 Quantities and units) and pertinent measuring methods.

The following shows, how you can download for instance the currency codes reliably into your own system through an XML schema totally based on standardized metadata:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="true"?>

<ISO_4217 Pblshd="2014-08-15">

<CcyTbl>

<CcyNtry>

<CtryNm>AFGHANISTAN</CtryNm>

<CcyNm>Afghani</CcyNm>

<Ccy>AFN</Ccy>

<CcyNbr>971</CcyNbr>

<CcyMnrUnts>2</CcyMnrUnts>

</CcyNtry>

In public eProcurement, in the building sector alone, the following metadata together with the respective codings occur: Measurement Method, Quantity Price, Variant Options, Price Type, Quantity Type, Information Status, Dimension Type, Query Type, Query Response Type, Communication Channel, Default Currency, Default Language, Tax Type, Units of Measure, Charge Category, Allowance or Charge Identification, Allowance or Charge Code Qualifier, Works Type, Project Type, Tendering Procedure, Work Item Type, Judging Criteria, Tender Invitation Revision, Entry Fee Indicator, Bill Of Quantities Type, Tendering Request, Breakdown Structure.

Often they comprise subsets of code elements from standardized codings. The code elements of the codings usually consist of the metadata name, abbreviation and a numeric tag. The reference data (or values) under each metadata again are specified by a name represented by its abbreviation and numeric tag. This also applies to the Trade Data Elements Directory (UNTDED) of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) which contains the standard data elements that can be used with any method for data interchange on paper documents as well as with other means of data communication. They can be selected for transmission one by one, or used within a particular system of interchange rules, e.g. the UN/EDIFACT standard. UNTDED comprises more than 1600 data elements (equiv. to metadata) with their unambiguous names and numeric tags. They can be grouped into 9 broad categories. The latest version of UNTDED does not include the service data elements, as these are provided today within the EDIFACT Syntax of multipart ISO 9735 Electronic data interchange for administration, commerce and transport (EDIFACT) – Application level syntax rules.

Beyond the above-mentioned internationally coded data, UNTDED recommends codings for: document names (and tags), codes for modes of transport, codes for abbreviations of INCOTERMS (containing shipment conditions such as ‘FoB’: free on board), location codes, special handling codes, etc.

In a list of code systems contained in a previous issue of the UNTDED nearly 400 codings are referenced with their unambiguous identifier. Needless to say that all airports, harbors, cities, companies involved in trade, containers etc. have coded representations. For most of the standardized (as much as possible unambiguously coded) metadata and codings there are registration authorities (RA) or maintenance agencies (MA) taking care of regular updating and maintenance of the data. All this is a world-wide huge cooperative effort of many stakeholders involved to avoid misunderstandings in eC/eB. The unambiguous (=language independent) letter and/or numeric tags do not hinder an enterprise of using names of the metadata or code elements in their national language(s).

For similar purposes, documents related to individual persons or organizations become more and more unambiguously structured so that they do not need translation any longer (as foreign language equivalents in many languages of the content elements of these documents are contained in networked databases). This also applies to the certification of documents by means of an ‘apostille’ whose structure and information is totally harmonized through the Hague Convention Abolishing the Requirement for Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents (also called Apostille Convention, or Apostille Treaty). The apostille is an international certification comparable to a notarisation in domestic law, and normally supplements a local notarisation of the document. The apostille (together with the document it refers to) issued in one of the signatory countries is recognized as certificate for legal purposes in all the other signatory states. In this connection it has to be mentioned that in spite of decades of efforts the international committee for the harmonization of addresses has not yet been able to come up with one unambiguous format of writing all addresses in the world – so far they arrived at two competing datamodels.

The bigger and diversified an organization and the wider the geographical outreach of its commercial activities, the more of the above-mentioned standards and standardized codings (or subsets of them) will have to be used in a systematic way.

Master data management (possibly carried out in different MDM system modules) provides a single source of truth of product data across the enterprise. The respective systems manage the definition and lifecycle of finished goods or services – collecting product data from multiple sources, securing agreement on the definition of products, distributing data downstream to a variety of systems and finally, publishing the information to web sites, marketing systems, merchandising systems, and more. To be successful, an organization requires a solution that can efficiently distribute key master data across various departments of an organization in a controlled manner with extreme accuracy.

3.6 Identification (ID) systems for microcontent

Like persons having a unique number on their citizenship card (or even several unique IDs for different purposes, such as for the national public health insurance or as a car driver), individual companies or products may have unique IDs. In the world of librarianship all kinds of numbering systems exist, such as the International Standard Book Number (ISBN). Increasingly content entities at the highest level of granularity are assigned unique IDs by commercial or non-commercial agencies also providing the ID resolution services.

The working group ISO/IEC-JTC 1/SC 32/WG 2 “MetaData” formulates the methodology standards on metadata and metadata registries (especially the ISO/IEC 11179 MDR series). International coordination groups are recommending the harmonization of a multitude of – often parallel – ID-systems for content items, which are a great barrier to the efficient interchange of structured content, especially in eC/eB. For such interchange a systematic approach is necessary, including checking processes, like verification, validation and certification etc. In product data management for eC/eB ISO/TS 29002-5:2009 “Industrial automation systems and integration – Exchange of characteristic data – Part 5: Identification scheme” is proposed as an open, non-proprietary standard as basis for applying an ID-system for product properties at the highest level of content granularity. The meta-standard ISO/IEC 9834-8:2014 “Information technology – Procedures for the operation of object identifier registration authorities – Part 8: Generation of universally unique identifiers (UUIDs) and their use in object identifiers” sets the rules and requirements of the respective ID registration authorities.

4. Conclusions and new requirements

The whole field of standardization has developed and grown to such an extent that

● It needs world-wide political meta-levels for coordinating certain standardization activities (e.g. in the form of the WTO, international legal instruments etc.),

● It requires new levels of meta-standards or legal instruments for harmonizing competing or even conflicting standards,

● New standardization fields emerge every year.

No wonder that standardization also has become a field of scientific research [see inter alia the activities of EURAS – the European Academy of standardization: http://www.euras.org/]

Methodology standardization and the standardization of an ever increasing number of content entities – especially those of microcontent (or structured content at the level of lexical semantics) – proved their usefulness

● To overcome the language barrier to quite some extent by means of language-independent approaches,

● To lay the theoretical and methodological basis for a next development stage in semantic interoperability, namely ‘content interoperability’.

However, the necessity for language and other kinds of inter-human communication not only remains, but is growing. As this growing need poses many difficulties, the number of content/data standards, as well as standards concerned with content-related methodology, language services, language technology, etc. continues to grow which results in lots of new enterprise internal and external content repositories. Some of them – among others due to their proprietary nature – cannot be integrated, but can and must be made interoperable.

The big challenge in enterprises today is to get away from hundreds of more or less insular databases with legacy data, and apply a systematic approach to content integration and interoperability. Content interoperability goes beyond mere re-usability and encompasses re-purposability. In this connection, multilingual resources of microcontent help to curb the increasing need for translation to some extent. In spite of lots of internationally unified structured content it will still and increasingly be necessary to have multilingual data in order to communicate within the enterprise and between branches of the enterprise in different countries – not to mention the communication with customers from different countries. Thus, many enterprises came to recognize that a ‘language policy’ is a useful, if not necessary, complement to a comprehensive content management policy.

Only fairly recently large enterprises became aware of the fact that it might be useful to re-use all kinds of microcontent for their learning management systems, because any individual content entity (even the metadata taken as a special kind of structured content) is potentially necessary to be re-purposed for the training of personnel. Therefore, a company with a strong need for systematizing its training activities is well advised to include the design of learning management systems into their comprehensive content and language policies.

Under the requirement of content integration and interoperability the quality of data is of highest concern. Once the process of data cleansing of legacy data is successfully completed, it needs a very systematic and accurate way of ensuring that the data are reliably maintained and updated either by own resources or through reliable external services. Mastering data and information quality management is a way to achieve efficient content management in the comprehensive and systemic form outlined in this contribution.

All of the above is of greatest importance for eCommerce/eBusiness and – for the sake of interoperability in the broadest sense – must be based on international standards. For countries with emerging economies, it is useful and advisable to look for and study best practices of eC/eB, in order to catch up fast and avoid mistakes which others have made in the course of implementing eCommerce.

References

BOIKO, B. (2004). Defining Data, Information, and Content. In: B. Boiko. Content Management Bible, 2nd Edition, pp. 3–12. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing Company.

CWA 15236:2005 Analysis of standardization requirements and standardization gaps for eProcurement in Europe.

CWA 15666:2007 Business requirement specification – Cross industry e-Tendering process.

CWA 16525:2012 Multilingual electronic cataloguing and classification in eBusiness – Classification Mapping for open and standardized product classification usage in eBusiness

GALINSKI, Ch. Wozu Normen? Wozu semantische Interoperabilität? [Why standards and why semantic interoperability?]. In: T. Pellegini and A. Blumauer, eds. Semantic Web – Wege zur vernetzten Wissensgesellschaft. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer, 2006, pp. 47–72. ISBN 10 3-540-29324-8, 13 978-3-540-29324-8; X.media.press ISSN 1439–3107.

GALINSKI, Ch. and H. BECKMANN. Concepts for Enhancing Content Quality and Accessibility: In General and in the Field of eProcurement. In: E. Kajan, F.-D. Dorloff and I. Bedini, eds. Handbook of Research on E-Business Standards and Protocols: Documents, Data and Advanced Web Technologies. Hershey PA, USA: IGI Global, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 84-101. ISBN 978-1-4666-0146-8 (hardcover), ISBN 978-1-4666-0147-5 (ebook).

GALINSKI, Ch. and B. S. GIRALDO PÉREZ. Typology of structured content in eApplications – under a content interoperability, quality and standardization perspective. IN: Gerhard Budin and Vesna Lušicky (eds.) Languages for Special Purposes in a Multilingual, Transcultural World. Proceedings of the 19th European Symposium on Languages for Special Purposes, 8-10 July 2013. Vienna: 2014. pp. 405-417. ISBN: 978-3-200-03674-1. (Available with Creative Commons NonCommercial 4.0 International License at: https://lsp2013.univie.ac.at/proceedings).

GALINSKI, Ch. and K. Van ISACKER. Standards-based Content Resources: A Prerequisite for Content Integration and Content Interoperability. In: K. Miesenberger et al., eds. ICCHP 2010, Part I, LNCS 6179. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag 2010, pp. 573–579. ISBN 3-642-14096-3.

GALINSKI, Ch. and D. REINEKE. Vor uns die Terminologieflut [Facing the terminology deluge]. In: eDITion, 2011, vol. 7, no. 2. pp. 8–12. ISSN 1862-023X.

Infoterm. Investigation of business-relevant standards and guidelines in the fields of the language industry. 2012 (ANNEX 2 to CELAN Deliverable D.2.1: Annotated catalogue of business-relevant services, tools, resources, policies and strategies and their current uptake in the business community).

International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). International Commercial Terms. 2010, Available at: http://store.iccwbo.org/incoterms-2.

ISO/IEC Directives 2014 (Part 1 Procedures for the technical work; Part 2 Rules for the structure and drafting of International Standards).

ISO/IEC Directives, Supplement. Consolidated procedures specific to ISO (2014) [including also Annex SQ (normative) Procedures for the standardization of graphical symbols and Annex SK (normative) Procedure for the development and maintenance of standards in database format].

ISO/IEC Directives, IEC Supplement, Procedures specific to IEC (2012) [including also Annex SK (normative) Implementation of the ISO/IEC Directives for the work on the IEC 60050 series – International Electrotechnical Vocabulary].

ISO/IEC Guide 2:2004 Standardization and related activities – General vocabulary.

ISO/IEC Directives, Supplement. Procedures specific to JTC 1 (2010).

ISO/IEC Guide 21-1:2005 Regional or national adoption of International Standards and other International Deliverables – Part 1: Adoption of International Standards.

ISO/IEC Guide 21-2:2005 Regional or national adoption of International Standards and other International Deliverables – Part 2: Adoption of International Deliverables other than International Standards.

MoU/MG-Management Group of the ITU-ISO-IEC-UN/ECE Memorandum of Understanding concerning eBusiness standardization) (2012). Recommendation on software and content development principles 2010 (MoU/MG/12 N 476 Rev.1) (Available at: http://isotc.iso.org/livelink/livelink/fetch/2000/ 2489/Ittf_Home/MoU-MG/Moumg500.html).

Text Encoding Initiative (TEI). TEI Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange (Available at: http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/).

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Trade Data Elements Directory (UNTDED) 2005 (equivalent to ISO 7372:2005) (Information on UNTDED and other trade facilitation instruments can be found under: http://tfig.unece.org/instruments.html).

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.0 Fifth Edition. (Available at: http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml/).

Annex

Recommendation on software and content development principles 2010

Purpose

This recommendation addresses decision makers in public as well as private frameworks, software developers, the content industry and developers of pertinent standards. Its purpose is to make aware that multilinguality, multimodality, eInclusion and eAccessibility need to be considered from the outset in software and content development, in order to avoid the need for additional or remedial engineering or redesign at the time of adaptation, which tend to be very costly and often prove to be impossible.

Background

In software development, globalization1, localization2 and internationalization3 have a particular meaning and application. In software localization they have been recognized as interdependent and of high importance from a strategic level down to the level of data modelling and content interoperability.

In 2005 the Management Group of the ITU-ISO-IEC-UN/ECE Memorandum of Understanding on eBusiness standardization adopted a statement (MoU/MG N0221), which defines as basic requirements for the development of fundamental methodology standards concerning semantic interoperability the fitness for

● multilinguality (covering also cultural diversity),

● multimodality and multimedia,

● eInclusion and eAccessibility,

● multi-channel presentations,

● which have to be considered at the earliest stage of

● the software design process, and

● data modelling (including the definition of metadata),

and hereafter throughout all the iterative development cycles.

The above requirements are a prerequisite for global content integration and aggregation as well as content interoperability. Content interoperability is the capability of content to be combined with or embedded in other (types of) content items and to be extensively re-used as well as re-purposed for other kinds of eApplications. In order to achieve this capability, software must support these requirements from the outset. The same applies to the methods and tools of content management – including web content management.

Recommendation

Software should be developed and data models for content prepared in compliance with the above-mentioned requirements to facilitate the adaptation to different languages and cultures (localization) or new applications (re-purposing), the personalization for different individual preferences or needs, including those of persons with disabilities. These requirements should also be referenced in all pertinent standards.

1 Globalization refers to all of the business decisions and activities required to make an organization truly international in scope and outlook. G11N is the transformation of business, processes and products to support customers around the world, in whatever language, country, or culture they require.

2 Localization is the process of modifying products or services to account for differences in distinct markets. Therefore, L10N is an integral part of G11N, and without it, other globalization efforts are likely to be ineffective. The interdependence of G11N and L10N has also been coined glocalization.

3 Internationalization is the process of enabling a product at a technical level for localization. An internationalized product does not require remedial engineering or redesign at the time of localization. Instead, it has been designed and built from the outset to be easily adapted for a specific application after the engineering phase.